In my last article, we discussed the main component of a game’s economy: resources. Lives, ammunition, cultural points, seeds and many other elements in physical and digital games can be understood as resources when we analyze a game’s economy.

From a practical standpoint, resources are useful in the game design process to define the game’s objective, i.e., how a player wins the game. This activity is straightforward when working with physical games. Take chess, for example; the necessary resource to win the game is the opponent’s king (a resource). Once a player captures the opponent’s king, the game ends. Check-mate.

Particularly, I use the terms victory resources or progression resources for these resources. Victory resources are those which grant victory to the players that acquire them, while progression resources are those that lead the player towards victory. There is a subtle difference between them, although you could similarly use them. This difference allows us to study game economies from different perspectives.

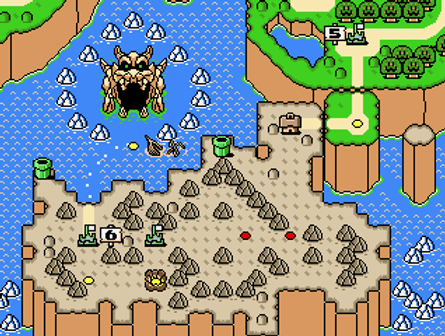

When playing chess, for example, the king is a victory resource: once a player captures it, this player wins; there are no clear progression resources since, at any moment, if a king is captured, the game ends, regardless of the board state. On the other hand, in a digital game such as Super Mario World, there are no clear victory resources, but there are well-defined progression resources: the game levels. As a player finishes a level, new levels are unlocked, leading towards the end of the game and saving Princess Peach.

Identifying victory and progression resources helps us in many ways. First, it helps us to understand which resources are immediately relevant to a player, as they more directly lead to victory. Second, these resources help us establish a clear objective for a game, which is a common hurdle in the first stages of game development. Third, and not least important, because they provide us with the base for the game’s progression.

The Journey as a Resource

Studying a game through the lens of collecting victory and progression resources allows us to see the games as an accumulation journey. A game’s progression, both in terms of rhythm and speed, is given by the accumulation of such resources. The rhythm establishes how much is accumulated at a time, while the speed establishes when the accumulation happens. Getting back to the Super Mario World example, we could say that the game progression is 1 level (rhythm) every 3 to 4 minutes on average (speed). I know some levels will take longer than 4 minutes, but you get the gist.

Controlling the rhythm and speed of a progression system allows us to plan when and how to use resources, activities and challenges. For example, a new mechanic might be introduced once the player achieves a certain progression state. We could design, let’s say, that, at every 10 levels, the player acquires a new ability to explore other areas of the game and unlock new resources, for instance.

More recent Super Mario instalments, such as Super Mario Odyssey, require the player to collect Power Moons to unlock new areas. That way, the game guarantees that a player has dedicated enough time and effort beating enough challenges to progress in the game.

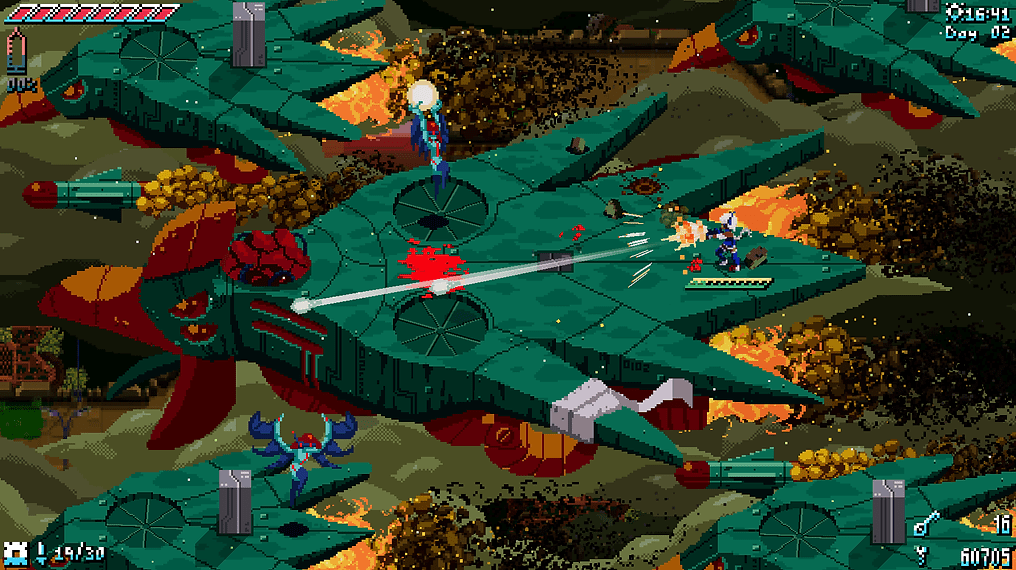

On the other hand, games with clear victory resources, like chess, are less likely to focus on progression and often present all their resources, activities, and challenges right from the start of the game. This is quite common in “open world games” in which the player skills are the main focus, such as From Software’s Elden Ring and Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Differently, these games can use the player’s creativity and knowledge to achieve non-linear progression, such as it is done by the Brazilian Pixel Punk studio on their game Unsighted.

Accumulation and Message

Beyond the practical study of resources in games, especially in terms of victory and progression resources, it is also important to understand the layers and subtext that are created by them.

Abstractly, resources are nothing more than numbers we collect through mechanics and mechanisms. However, concretely, resources are intrinsically related to many other aspects of the game, such as the game’s narrative and message. Getting back to the Super Mario Odyssey example. The Power Moons are not only numbers but also the actual fuel that allows Mario to chase Bowser, the villain, and save the damsel in distress, Princess Peach.

From a game design perspective, the Power Moons allow training and challenge of the players’ abilities so they match the game’s difficulty progression. From a narrative perspective, the Power Moons fuel the Odyssey’s engine so it can fly to new worlds and stories. Under the hood, Power Moons are an accumulation of heroic male feats on a journey to save a defenceless female.

Surely, this article is not focused on problematizing Super Mario games but on pointing out how resources hold more meaning than just numerical representations. In general, progression-based games tend to promote a positive accumulation ideal, reinforcing the liberal notion of extractivism as a synonym for progress and evolution. In games of this sort, it is common to continuously engage in the extraction and transformation of resources to progress, as if the only possible and feasible way of developing is through material transformation.

Building and exploration games, such as the beloved Terraria, are based on this continuous loop of exploration, extraction, transformation, and progress. While it is fun and engaging for the constant loop of challenges and progression, which empowers and entertains the player, there is a hidden message that the explored and exploited planet, its inhabitants, and its resources are the only means to propel the protagonist’s ascension. Again, this article is not meant to problematize Terraria or other games with similar systems but to point out what some of these games’ messages and mechanics are stating.

Studying and understanding these messages allows us to reflect on how we use resources in our games and what is the meaning of their progressions. Besides that, it helps us to realize when we are creating something new, with a message we stand behind, or when we are simply repeating a message that we have been fed without even realizing it.

So, what is the message from your game? And which messages and stories are your resources telling your players? Were you the designer who chose them, or did someone else do it for you?

Thanks for reading, and see you soon 😉

References:

Serpa, Y. R. (2024). The Cores of Game Design: Mechanics, Economics, Narrative, and Aesthetics. CRC Press.

Adams, E., & Dormans, J. (2012). Game Mechanics: Advanced Game Design. New Riders.

| This article is also available in Brazilian Portuguese on the Controles Voadores website. You can access it via the link: Game Economics 101 |