Games are composed of many parts: narrative, technology, audiovisual elements, boards, mechanics, etc. Many authors explore these aspects in an attempt to define an ideal anatomy for games, besides many online posts and general discussions on which are the main and most important elements of a game. Often, mechanics are the most popular pick, generally being mentioned as the element that distinguishes games from other media, as mechanics allow the interaction between player and play, something we do not see in other media*.

However, other important elements in game design and development are worthy of attention, such as narrative and aesthetics. Furthermore, an important aspect that is often ignored is the economy. In game design, the idea of the game economy is not related to market models or budget management of game production, although those are certainly important aspects. The game economy is the game design field that deals with game resources, as well as their relations and mechanisms.

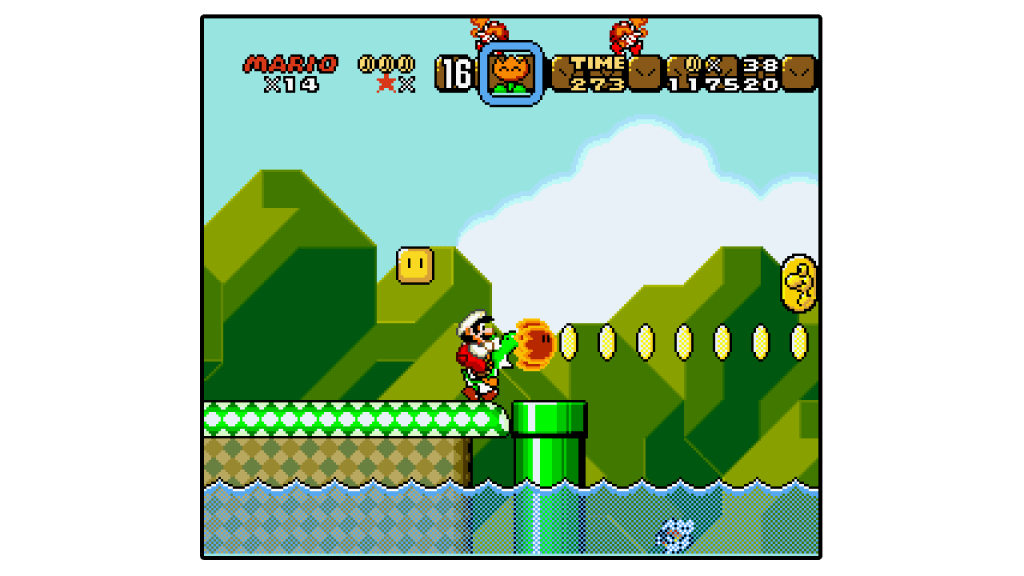

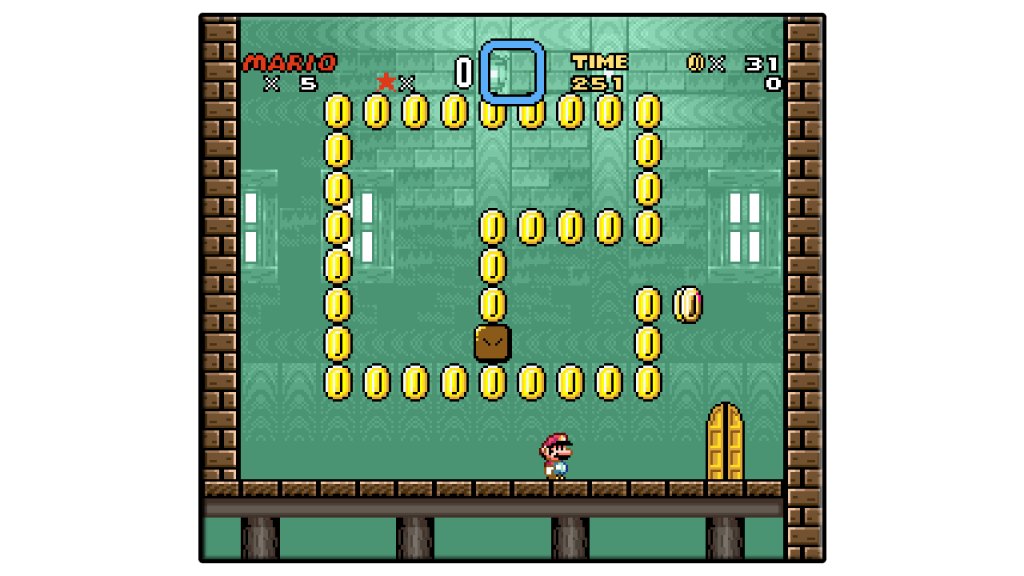

By definition, resources are any element in the game that can be represented numerically. By that, we refer to any sort of counting, even if it is just a binary counting (0 or 1). For example, in an adventure game such as Super Mario World, lives and coins are resources. But whether or not you have Yoshi is also a resource. In this case, a binary resource: either the player has Yoshi (1) or does not (0).

Resources interact with the game mechanics, but they are not restricted to specific mechanics. Getting back to the previous example, if Mario jumps onto a platform and gets a green mushroom, then the player gets uma extra life (increments the life resource). At the same time, if 100 coins are collected, those are converted into 1 life. Notice that in both situations, we are dealing with the same resource (life) but through different mechanics and systems.

Resources may also appear in multiple forms, changing their characteristics. There are many coins physically spread in all levels of Super Mario World, which assume a new form of a number in the game’s interface once the player collects them. The number of coins in the game’s interface displays the amount of collected coins, but this number is not the same as the physical coin we see on a level. Those are different forms in which the same resource can take.

This distinction is a powerful tool for game design possibilities. The same immaterial coins in the interface, for example, are part of the mechanism that converts them into a new life once their number reaches 100 coins. However, the physical coins in the levels do not participate in this mechanism and have their own mechanics. For example, some mechanisms in the game spawn timed physical coins that disappear after some time. Some other mechanisms transform those physical coins into blocks, allowing the player to find new paths and use them as platforms.

These different manifestations allow for different mechanics and mechanisms. Knowing that there are shortcuts or secret rooms, the player might choose not to pick up some physical coins in the level and transform them into blocks, for example, something that is not possible once they are collected and changed to their immaterial form in the game’s interface.

Tangible and Intangible Resources

The term we use to describe the physical characteristics of a resource is its tangibility. A tangible resource exists physically in the game world, while intangible resources do not and appear in the game through visual interfaces or other visual elements outside the physical laws of the game.

As previously discussed, the tangibility of a resource is a powerful game design tool. An interesting exercise using this concept is inverting the tangibility of resources to create unique situations.

For example, in Super Mario World, we could propose a new mechanic that increases Mario’s size based on the player’s current score. Mario’s body would work as a physical manifestation of the player’s score, making it tangible in a way that impacts its mobility. The higher the score, the bigger Mario’s body and the higher the chances of it being hit by obstacles and hazards. On the other hand, smaller scores would lead towards easier gameplay but reduce the chances of the player getting other resources, such as lives, which are dependent on the player’s score.

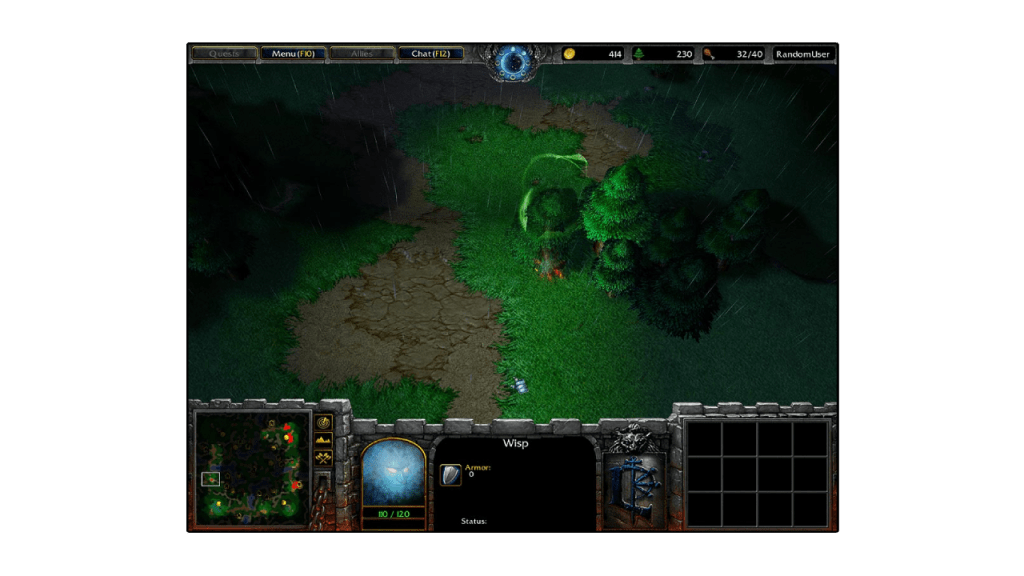

Real-time strategy games explore the tangibility of their resources in many interesting ways. Trees, for example, are always good study cases. Generally, physical trees in the game world have to be harvested and taken back to the player’s base to be collected, transforming into their intangible form in the game’s interface. Once in their intangible form, these trees are safe from other players and can be used by other mechanisms of the economy. On the other hand, in their tangible form, trees are vulnerable to being attacked by an opposing player using combat mechanics, such as bombs and other area-of-effect attacks. Besides that, different collecting mechanics can be used to explore the tangible properties of these trees, even in non-destructive approaches, allowing the trees to act as a sort of “natural” wall that protects and hides the player’s base.

In Warcraft III, for example, the Wisp unit is capable of harvesting lumber from trees without destroying them and even without returning to the base to store them. Their harvesting process is done automatically in place and also thematically fits the idea of the Night Elves race, which lives in harmony with nature and the woods.

But Not All Resources are Relevant

Still, even if the definition states that any aspect that can be numerically represented can be understood as a resource, not all resources are worth our attention. Walls and corridors, for example, as decoration plants and scenario details, are technical resources, as they fit into the definition but are hardly connected to mechanics and mechanisms in any meaningful way. It is the game designer’s task to define which resources are relevant to the game and use them as tools to work other aspects of the game, such as the mechanics that use them or the mechanisms that transform them.

On the other hand, exploring these often ignored resources can be a valid and creative source. What if we used walls and corridors as part of our main mechanics? What if the scenario details were meaningful to the game’s narrative beyond their aesthetical values? Exploring these and other aspects and resources can lead to innovative economies and expand the creative possibilities of the game development process. And, even if you do not develop games yourself, studying and analysing economies can help you expand the notions from which you admire them.

Understanding and studying resources is also an important tool in analysing the message of a game. Which resources are truly explored by the game? What is their message? Is it a message of greedy accumulation and speculation? Well, we will continue discussing this in another piece.

Thanks for reading, and see you soon 😉

References:

Adams, E., & Dormans, J. (2012). Game Mechanics: Advanced Game Design. New Riders.

| This article is also available in Brazilian Portuguese on the Controles Voadores website. You can access it via the link: Game Economics 101 |